On Sunday, Rajya Sabha passed two of the three farm reforms Bills that have seen widespread protests in recent weeks, particularly in Haryana and Punjab, where the ruling BJP has lost its ally Shiromani Akali Dal. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has reiterated that farmers will benefit from the changes, first mentioned as part of the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan package. The Bills replaced three ordinances promulgated earlier.

So, think of “The Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020” as the APMC Bypass Ordinance. Treat “The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020” as “The Freedom of Food Stocking by Agribusinesses Ordinance”, and “The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020” as the Contract Farming Ordinance.

On paper, what the first one attempts to do is allow farmers to sell their produce at places other than the APMC-regulated mandis. It is crucial to note that the idea is not to shut down APMCs but to expand a farmer’s choices. So, if a farmer believes a better deal is possible with some other private buyer then he can take that option instead of selling in the APMC mandi.

The second Bill proposes to allow economic agents to stock food articles freely without the fear of being prosecuted for hoarding.

The third Bill provides a framework for farmers to enter into contract farming — that is signing a written contract with a company to produce what the company wants in return of a healthy remuneration.

The idea with all three Bills is to liberalise the farm markets in the hope that doing so will make the system more efficient and allow for better price realisations for all concerned, especially the farmers. The central concern, presumably, is to make Indian farming a more remunerative enterprise than it is right now.

There are two diametrically opposite ways to look at these changes.

One is to believe that the plan on paper will operationalise perfectly in real life. This would mean farmers will get out of the clutches of the monopoly of APMC mandis and evade the rent-seeking behaviour of the traditional intermediaries (called arhatiyas). A farmer would be able to pick and choose who to sell to, and at what price, after making an informed decision. And that, most crucially, when he does this, more often than not, he will end up earning more than what he typically did in the past when he sold his produce through the “exploitative” arhatiyas in the APMC mandis.

The polar opposite viewpoint, from the protesters, is that this move towards greater play of free markets is a ploy by the government to get away from its traditional role of being the guarantor of minimum support prices (MSPs). To be sure, MSPs work in the formally regulated APMC mandis, and not in private deals.

Farmers, especially in Punjab and Haryana where MSPs are more prominently employed, are suspicious of what the markets will offer and how the “big companies” will treat them. Farmers can influence the most powerful governments through the electoral process but vis-a-vis big companies, they are exposed as minor players, incapable of bargaining effectively.

There are no easy answers apart from saying that while both have some valid points, neither view is fully correct.

For instance, the new laws are not shutting down APMC mandis, nor are they implying that MSPs will not be functional. Moreover, it is true that — across several sectors of the economy — liberalisation has expanded the size of the pie and improved wellbeing across the board.

Why should a farmer not have more choices? If the private deal is not distinctly better, a farmer can carry on as before. If corporate farming does manage to weaken the APMC mandi system, it would only be because hordes of farmers chose corporate farming or selling outside existing mandis. Could it be the case that the arhatiyas and existing elites are the ones who are threatened by this reform?

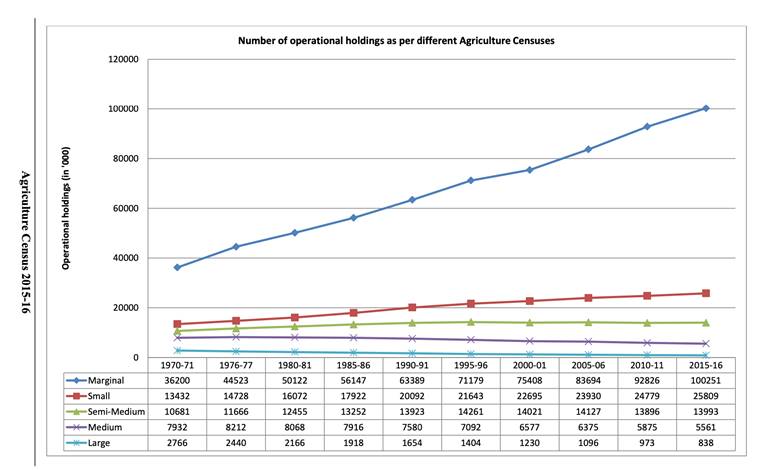

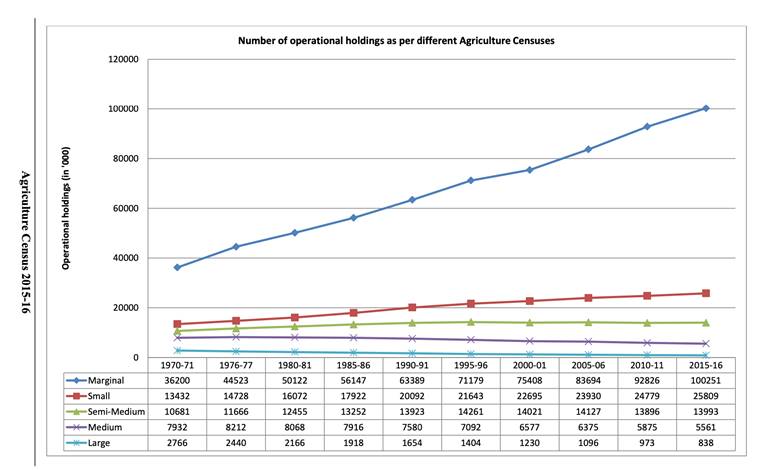

Moreover, there is an unwarranted fascination with MSPs in India. The last Agriculture Census (2015-16) showed that 86% of all land holdings were small and marginal (less than 2 hectares); see Chart. These are such small plots that most farmers dependent on them are net buyers of food. As such, when MSPs are raised they tend to hurt the farmers the most.

This is notwithstanding the data that shows more and more farm produce is being sold to private players — instead of the government via MSPs — already.

On the other hand, one can understand why farmers are so sceptical about markets. A good example is what happened when the government enforced a ban on onion exports. In doing so, the government prioritised the interests of the consumers over the interest of the farmers (the producers).

This is not the first time. There are innumerable past examples when the government’s decision to protect the consumers from higher prices have resulted in farmers being robbed of the higher prices a free market could have provided them. In fact, the MSP, it can be argued, is the embodiment of this distrust.

Another underlying structural problem is the lack of information with farmers, which inhibits their ability to make the best decision for themselves. For instance, how will an average farmer figure out the right price for his or her produce?

Similarly, in the absence of adequate infrastructure to store their produce, farmers may not have the capacity to bargain effectively even if they knew the right price.

In the end, what will determine the results of this latest set of reforms will be their implementation.

If farmers feel robbed and exploited when they participate more fully in the market, they will blame the political masters. But, if they taste success via better returns on a sustained basis — higher profits that allow them to afford better standards of living — then several long-standing doubts and misgivings about markets and these reforms will melt.

What do the Bills do?

The first thing to do is to simplify the names of these ordinances as agriculture economist Sudha Narayanan (of the IGIDR) has done.

So, think of “The Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020” as the APMC Bypass Ordinance. Treat “The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020” as “The Freedom of Food Stocking by Agribusinesses Ordinance”, and “The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020” as the Contract Farming Ordinance.

On paper, what the first one attempts to do is allow farmers to sell their produce at places other than the APMC-regulated mandis. It is crucial to note that the idea is not to shut down APMCs but to expand a farmer’s choices. So, if a farmer believes a better deal is possible with some other private buyer then he can take that option instead of selling in the APMC mandi.

The second Bill proposes to allow economic agents to stock food articles freely without the fear of being prosecuted for hoarding.

The third Bill provides a framework for farmers to enter into contract farming — that is signing a written contract with a company to produce what the company wants in return of a healthy remuneration.

The idea with all three Bills is to liberalise the farm markets in the hope that doing so will make the system more efficient and allow for better price realisations for all concerned, especially the farmers. The central concern, presumably, is to make Indian farming a more remunerative enterprise than it is right now.

How have they been received?

There are two diametrically opposite ways to look at these changes.

One is to believe that the plan on paper will operationalise perfectly in real life. This would mean farmers will get out of the clutches of the monopoly of APMC mandis and evade the rent-seeking behaviour of the traditional intermediaries (called arhatiyas). A farmer would be able to pick and choose who to sell to, and at what price, after making an informed decision. And that, most crucially, when he does this, more often than not, he will end up earning more than what he typically did in the past when he sold his produce through the “exploitative” arhatiyas in the APMC mandis.

The polar opposite viewpoint, from the protesters, is that this move towards greater play of free markets is a ploy by the government to get away from its traditional role of being the guarantor of minimum support prices (MSPs). To be sure, MSPs work in the formally regulated APMC mandis, and not in private deals.

Farmers, especially in Punjab and Haryana where MSPs are more prominently employed, are suspicious of what the markets will offer and how the “big companies” will treat them. Farmers can influence the most powerful governments through the electoral process but vis-a-vis big companies, they are exposed as minor players, incapable of bargaining effectively.

Which view is correct?

There are no easy answers apart from saying that while both have some valid points, neither view is fully correct.

For instance, the new laws are not shutting down APMC mandis, nor are they implying that MSPs will not be functional. Moreover, it is true that — across several sectors of the economy — liberalisation has expanded the size of the pie and improved wellbeing across the board.

Why should a farmer not have more choices? If the private deal is not distinctly better, a farmer can carry on as before. If corporate farming does manage to weaken the APMC mandi system, it would only be because hordes of farmers chose corporate farming or selling outside existing mandis. Could it be the case that the arhatiyas and existing elites are the ones who are threatened by this reform?

Moreover, there is an unwarranted fascination with MSPs in India. The last Agriculture Census (2015-16) showed that 86% of all land holdings were small and marginal (less than 2 hectares); see Chart. These are such small plots that most farmers dependent on them are net buyers of food. As such, when MSPs are raised they tend to hurt the farmers the most.

This is notwithstanding the data that shows more and more farm produce is being sold to private players — instead of the government via MSPs — already.

On the other hand, one can understand why farmers are so sceptical about markets. A good example is what happened when the government enforced a ban on onion exports. In doing so, the government prioritised the interests of the consumers over the interest of the farmers (the producers).

This is not the first time. There are innumerable past examples when the government’s decision to protect the consumers from higher prices have resulted in farmers being robbed of the higher prices a free market could have provided them. In fact, the MSP, it can be argued, is the embodiment of this distrust.

Another underlying structural problem is the lack of information with farmers, which inhibits their ability to make the best decision for themselves. For instance, how will an average farmer figure out the right price for his or her produce?

Similarly, in the absence of adequate infrastructure to store their produce, farmers may not have the capacity to bargain effectively even if they knew the right price.

Where is all this heading to?

In the end, what will determine the results of this latest set of reforms will be their implementation.

If farmers feel robbed and exploited when they participate more fully in the market, they will blame the political masters. But, if they taste success via better returns on a sustained basis — higher profits that allow them to afford better standards of living — then several long-standing doubts and misgivings about markets and these reforms will melt.

Comments

Post a Comment